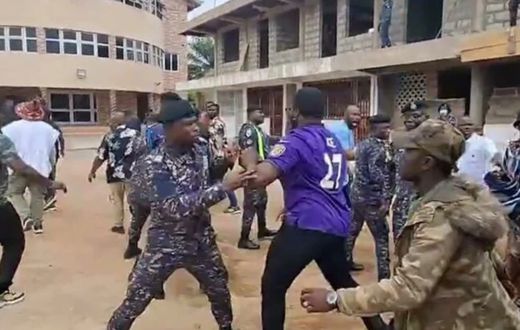

By-elections in Ghana are supposed to be routine democratic exercises, filling vacant parliamentary seats between general polls. Instead, they have become battlegrounds.

What should be an orderly process of casting ballots frequently collapses into scenes of chaos: young men brandishing clubs and stones, vehicles set ablaze, polling stations besieged.

From the bloody confrontation in Ayawaso West Wuogon in 2019, to the violent clashes in Odododiodioo in 2021, to the more recent turmoil in Ablekuma North in 2025, the pattern is depressingly familiar. And at the centre of it all are Ghana’s youth, disproportionately present as both perpetrators and victims.

“These are not random acts of hooliganism. They are the result of systemic exploitation of young people by political elites,” said Dr. Kojo Asante, Director of Advocacy at CDD-Ghana.

A Democratic Jewel Under Strain

Ghana has long been hailed as one of Africa’s strongest democracies, earning praise for peaceful transitions of power in a region often plagued by coups and contested elections. Yet the cycle of by-election violence has tarnished that reputation.

The problem is not new. From Chereponi in 2009 to Atiwa in 2010, Talensi in 2015, and beyond, violence has shadowed these contests. The stakes have grown higher since 2020, when a closely divided Parliament turned every by-election into a fight that could tip the balance of power.

“In a hung parliament, one seat can change everything,” said Franklin Cudjoe, founder of the policy institute IMANI Africa. “

How the Cycle of Violence Works

The machinery of by-election violence is as predictable as it is corrosive. Political financiers and local party operatives bankroll youth groups, offering cash, food, alcohol, and sometimes weapons in exchange for loyalty. For many young men confronting limited economic prospects, the offer is difficult to refuse.

With youth unemployment estimated at over 12 percent, and far higher among those under 25, party mobilization becomes an economic opportunity. It is a transaction: short-term rewards today, with vague promises of jobs or contracts tomorrow.

Read Also: UCC Holds Orientation for Fresh Sandwich Students

Layered on top of this economic vulnerability is identity politics. In constituencies with strong ethnic or regional divides, politicians often inflame tensions, portraying opponents as existential threats. And because prosecution rarely reaches beyond the foot soldiers on the ground, organizers operate with impunity.

Jean Mensa, chair of the Electoral Commission in a 2023 address warned that “By-elections should not be treated as life-and-death contests, when violence keeps women, the elderly, and vulnerable voters away, we undermine the legitimacy of the process”.

Lives on the Frontlines

For the youths themselves, involvement in by-election clashes is rarely ideological. More often, it is about survival and belonging.

Kweku, a 23-year-old in Accra, described how he was recruited: “They came with money, food, and promises. Some of us thought it was our chance to get ahead. But after the fighting, nothing changed. Only scars and police trouble.”

Another, Mohammed from Tamale, said joining a party youth wing at 19 gave him a sense of identity. “But during a by-election, I lost two friends. They died, and no one was held responsible. Now I feel used.”

These personal stories illustrate a broader tragedy: young people lured into cycles of violence that leave them poorer, traumatized, and excluded from the very democracy they were told they were defending.

The Warnings From Above

Prominent voices in Ghanaian politics and civil society have sounded alarms.

“Democracy is being stolen through violence and intimidation,” said Sammy Gyamfi, national communications officer of the opposition National Democratic Congress (NDC).

Samuel Okudzeto Ablakwa, an outspoken NDC Member of Parliament, has called the exploitation of youth “a dangerous affront to democracy.”

On the government side, Kojo Oppong Nkrumah, then minister of information, acknowledged “excesses” during the Ayawaso violence of 2019 but promised reforms.

Civil society leaders, including the Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO), have pressed for more decisive action: “It is time to pursue the financiers, not just the foot soldiers,” one senior official said.

Even judges have spoken. Justice Emile Short, who chaired the commission of inquiry into Ayawaso, stressed that “the failure to prosecute sponsors is the critical enabler of recurring violence.”

A Regional Mirror

Ghana’s struggles mirror broader trends in West Africa, where young people are routinely drawn into political clashes. Nigeria’s elections have long been marred by party “thugs.” Sierra Leone’s 2018 and 2023 polls saw youth-led street battles.

The toll of by-election violence is profound. Lives are lost. Young men are left disabled or with criminal records that shadow them for life. Small businesses are destroyed. Communities are split along partisan and ethnic lines.

At the national level, each episode chips away at Ghana’s democratic image.

Samson Lardy Anyenini, a legal analyst and broadcaster once said “We are teaching a generation that political success comes not from ideas or service, but from force”.

Attempts at Reform

Parliament passed the Vigilantism and Related Offenses Act in 2019, outlawing party militias. The Emile Short Commission made sweeping recommendations after Ayawaso, including prosecuting financiers and reforming security operations.

But enforcement has lagged. “

Analysts and civic leaders agree that ending the cycle requires urgent, multipronged action. Prosecutions must target not just the youths but also their political sponsors. Parties must be sanctioned, even deregistered, if found complicit.

Economic empowerment programs must create real alternatives for young people, reducing the allure of quick political rewards. Civic education should confront the manipulation of youth head-on, equipping them to resist exploitation.

And by-elections themselves must be treated with the same seriousness as national polls, with security agencies deploying intelligence-driven strategies to prevent escalation.

A Crossroads for Democracy

Ghana’s by-elections have become a litmus test for its democratic resilience. Each one poses the same question: will the country continue sacrificing its youth to partisan ambition, or will it reclaim their energy for nation-building?

“Ghana’s youth are not the problem, they are victims of a political system that sees them as pawns” said a senior official with CODEO.

According to him, the cost of inaction is a democracy that slowly bleeds credibility, one by-election at a time.”

The future of Ghana’s democracy, many warn, depends on breaking this cycle. The stakes could not be higher.

As we head towards the by elections in Akwatia and Tamale Central, it is the hope of every Ghanaian that these will not bring any violence but unity.

Source: Eric Arthur, MPhil Student at the Department of Communication Studies, UCC