A myth among the Efik people of southern Nigeria is that one of their 19th Century kings was married to Queen Victoria of England.

“I first heard about it around 2001, when I was going through the museum and saw this very interesting correspondence between Queen Victoria and King Eyamba,” said 60-year-old Donald Duke, who carried out extensive renovations on the national museum and also established a slave trade museum in the Cross River state capital city of Calabar, when he was governor there from 1999 to 2007.

“I thought it was important that we document our history, so we did a lot of research,” he said.

King Eyamba V was one of two monarchs based in the coastal town of Calabar, then made up of two sovereign states.

King Eyamba V of Duke Town and King Eyo Honesty II of Creek Town presided over the affairs of the Efik ethnic group in the mid-19th Century, and controlled commerce with European merchants.

Owing to their location along the coast, the Efik developed long-standing relations with the Europeans, which greatly influenced their culture.

They often bear English surnames, such as Duke and Henshaw, and the traditional clothing of the men and women is similar to British fashions of the Victorian era.

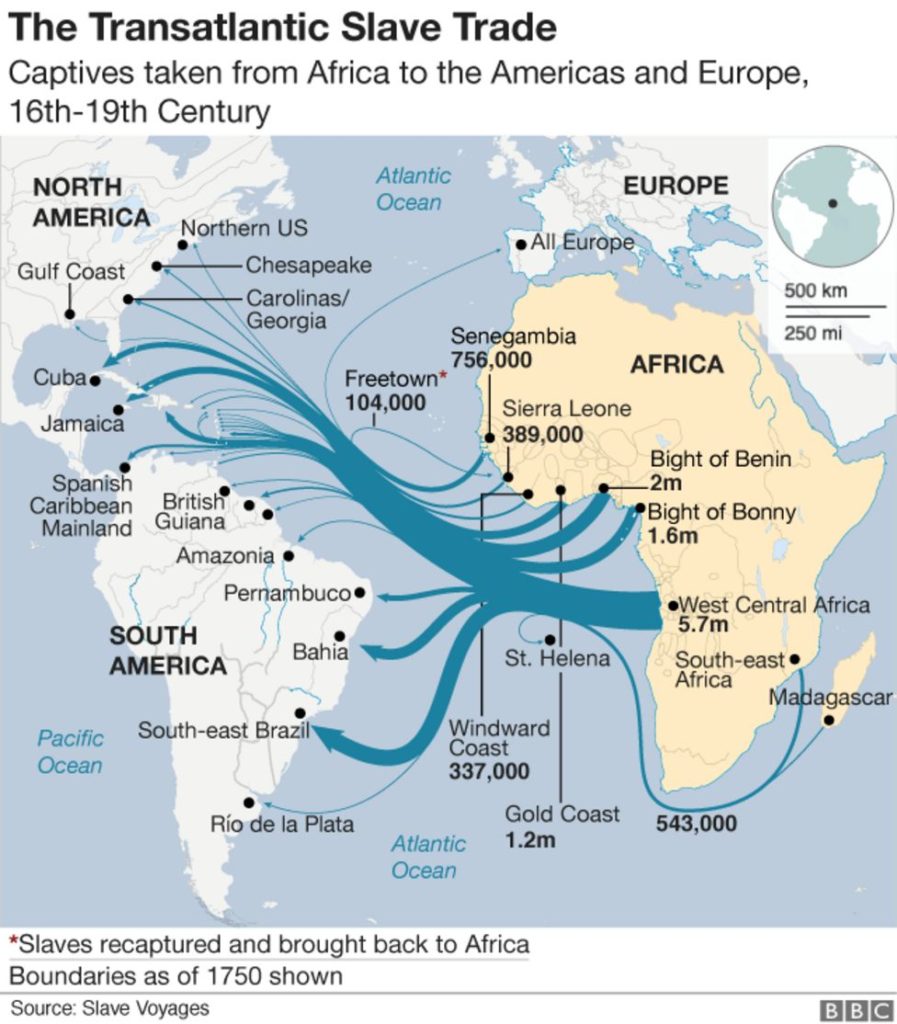

The Efik also dominated the slave trade. They acted as middlemen between the African traders from the hinterlands and the white merchants on ships mostly from English cities such as Liverpool and Bristol.

They negotiated prices for slaves, then collected royalties from both the sellers and buyers. They worked on the docks, loading and offloading ships, and supplied the foreigners with food and other provisions.

“The kings became very wealthy. The families became prominent. They controlled the largest trough of slaves coming out of Africa,” Mr Duke said.

Eyewitness account of slave trader

More than 1.5 million Africans were shipped to what was then called the New World – the Americas – through the Calabar port in the Bight of Bonny, making it one of the largest points of exit during the transatlantic trade.

A book containing the 18th Century journal of an Efik slave trader – written in Pidgin English and discovered in Scottish missionary archives – was published in 1956.

Titled The Diary of Antera Duke, it is the only surviving eyewitness account of the slave trade by an African merchant.

“We went down with Tom Cooper and the captain of Comberbach tender and we got on board at 2 o’clock and settled everything, and he dashed duke and us 143 kegs of powder and 984 coppers,” one entry reads.

Decades after the slave trade was abolished in Britain in 1807, human cargo was still transported to other countries through Calabar.

“It was important that Queen Victoria had the kings of Calabar on her side,” Mr Duke said.

“She wrote a letter asking that they stop trading in people and start trading in spices, palm oil, glassware, and other things.”

This is where the myth begins.

In her letter to King Eyamba, Queen Victoria offered inducements that included protection to him and his people.

She then signed off as “Queen Victoria, The Queen of England”, which a local interpreter incorrectly relayed as “Queen Victoria, The Queen of All White People”.

King Eyamba decided that if he was going to accept protection from a woman, then they had to get married. He told her so in his written reply, and signed off as, “King Eyamba, the King of All Black Men”.

“He was adventurous and dictatorial,” said Charles Effiong Offiong-Obo, an Efik chief who is also the current scribe of the Duke Town clan.

“He wrote to the Queen and said he wanted to marry her so that the two of them would rule the world.”

One can only imagine Queen Victoria’s reaction on reading King Eyamba’s letter. But she did not explicitly decline his offer.

“She acknowledged the king’s letter and said she looked forward to having good trade relations with him,” Mr Offiong-Obo said.

Her letter was accompanied by some gifts – including a royal cape, a sword, and a Bible – a goodwill gesture that King Eyamba interpreted as acceptance of his marriage offer.

Thus, the people began to believe that their king had married the queen.

Copies of correspondence between Queen Victoria and Kings Eyamba and Honesty are on display at the National Museum in Calabar, a building that was once the seat of the British colonial administration of southern Nigeria.

Some of the original letters have been sold to an unnamed private collector, I was told by a staff member of Between the Covers Rare Books Inc, which handled the sale.

Some time in the 20th Century, the Efik people agreed that only one monarch, known as an obong, would represent them, thus merging the thrones once occupied by Kings Eyamba and Honesty.

Prince becomes ‘in-law’

Prince Michael of Kent was on a brief private visit to Calabar in 2017, when the reigning Obong, Edidem Ekpo Okon Abasi Otu V, learned that the people’s in-law from England was in town.

He feted the prince – a member of the British royal family and first cousin of Queen Elizabeth II – and made him a chief with the title Ada Idagha Ke Efik Eburutu, meaning “A person of honour and high standing in the Efik Eburutu Kingdom”.

Barbara Etim James, an obong-awan, or queen, among the Efik recalls that she was given just two days to plan the grand ceremony to confer the title, which took place at the obong’s palace.

“During Prince Michael’s visit from England, at every opportunity, they reminded him that he was their in-law. Even at the ceremony, they told that story again,” she said.

“Prince Michael was delighted to hear the historical ties between the Efik and British royalty and was honoured to be deepening those ties with his Efik chieftaincy,” she added.

In keeping with the tradition that began following King Eyamba’s “marriage” to Queen Victoria, the coronation of the Obong of Calabar still takes place in two phases.

After the traditional rites are concluded in the community, the coronation ceremony continues in a Presbyterian Church (formerly the Church of Scotland), where the obong wears a crown and cape custom-made for the occasion in England.

Two thrones are set side by side and he sits on one, while the second is left empty for the absent Queen of England (or a Bible placed on it). His known wife sits behind him.

“Here we have a union between the Queen of all White People and the King of all Black Men,” Mr Duke said.

Read Also: ‘Our mission is to institutionalize the ‘culture of protest’ in Ghana,’ – #FixTheCountry convenors

SOURCE: BBCAFRICA